|

On a gray, dismal day, cloudy but calm, the s.s. Poet departed the Delaware coast of the United States, October 24, 1980. At 9 a.m. Captain Leroy Warren sent:

DEPARTURE CAPE HENLOPEN, 24, 0830 BUNKERS RECEIVED 4157 SAILING 6218 ETA PORT SAID 090600

It was a typical message informing both her owners and the Maritime Administration of her position and time of arrival at her destination. He also transmitted she would be following a Rhumb Line course to Gibraltar (crossing all meridians at the same angle on a Mercator chart). Her cargo was #2 yellow corn. Her speed 15 knots.

The Poet then left the shoreline, never to be seen again. She was heard from briefly at midnight. This was from the third mate, Robert Gove, when he called his wife on ship-to-shore radio. He mentioned nothing to her but the basics of the trip and that all was well. Again, nothing seems unusual.

According to her owners, Hawaii Eugenia Co, the Poet was to transmit her fuel and position reports on Mondays and Thursdays. Every 48 hours she was to send her USMER (U.S. Merchant Vessel Locator Filing System) reports to the Maritime Administration in Washington D.C.

When this last report was due, on the 26th of October, nothing was heard from the Poet. She was apparently gone, an 11,421 ton ship with a 13,500 ton cargo and 34 crew. She sent no SOS. Nor was there any identifiable EPIRB signal, although there was a brief few second signal that suddenly stopped. This was on the 26th. Earl Johnson, marine radio operator at WHM radio in Baltimore, recalls: “I heard an auto alarm signal or portions thereof consisting of 4 to 6 four-second dashes at one-second intervals on 500 kHz. The auto alarm signal was clear but weak. The signal did not fade in or out but was steady and then abruptly ended.” If this was from the Poet, it would place her right were others had vanished north of Bermuda, at the edge of the Sargasso Sea.

The search for the Poet was massive, initiated on November 3rd when the owners informed the Coast Guard she was overdue in her regular communications.

. . .During the next 5 days, the Coast Guard conducted extensive communication checks with negative results. An air and surface search was commenced on 8 November and the ensuing search, which covered over 296,000 square miles during a 10 day period, proved unsuccessful . . . No trace of the vessel, crewmen, or debris was ever found.

There is no easy answer to the disappearance of such a huge vessel without trace, though certainly the ocean was given enough time to disperse debris. The owners should have reported her overdue sooner. The delay in the Coast Guard search was the direct result of this. Without knowing where the ship could have vanished, the Coast Guard had to try and narrow down its field of search with radio checks. None of this proved useful, however, and the search had little chance of even pinpointing a spot.

However, none of this explains what could have happened to her to begin with. Several novel theories were offered, though officially dismissed. One concerned her cargo of corn. If it got wet, some wondered if it might have expanded and ruptured the hull. Another theory was based on the words of Coleman O’Donoghue, who claimed that Noel McLaughlin, the ship’s baker, told him that the Poet was a “bucket of rust.” He added: “We heard some people on deck say she wasn’t seaworthy.”

This type of comment is so typical after a major disappearance, it is surprising it is considered newsworthy anymore.

Part of the job of the Marine Board of Inquiry is to determine the vessel’s condition. The Board convenes at varying locales depending on the location of the disaster. From their meeting place they sift out evidence gleaned by a number of investigators sent to key places to locate pertinent records: where the vessel was built, the yards where it was repaired, surveyed, overhauled; certificates of inspection and repairs, etc. Witnesses are called to give firsthand recall of the ship’s past. Expert and eyewitness testimony is introduced and heard. Basically, the ship is on trial. In this particular case, the Marine  Board convened at Norfolk, Virginia. And a major part of their job was to determine seaworthiness. Considering there was absolutely no tangible remains to go on, clues had to be sought from her past. Board convened at Norfolk, Virginia. And a major part of their job was to determine seaworthiness. Considering there was absolutely no tangible remains to go on, clues had to be sought from her past.

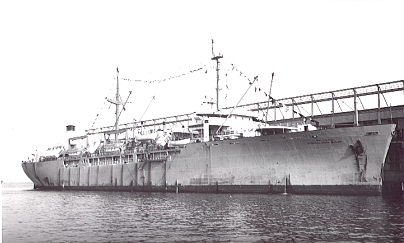

The Poet during WWII as the General Omar S. Bundy.

In August, 1980, the Poet’s hull had been inspected and found in good condition. That same month the government did its annual load line check, and the FCC inspected and passed her telegraphy equipment. Earlier in March the Poet had passed her biennial, dry-dock and tailshaft inspection by the Coast Guard. And in October before she sailed the CG inspected and passed all her safety and navigational equipment. The Poet had sustained minor damage to her portside hull in Matidi Harbor, Zaire, in 1978, but the inspector did not feel it was serious enough to warrant immediate attention. The dents were filled with cement and the ship could wait until her next drydocking.

However, there was an ongoing problem with hatch No.1. Had it given way under heavy weather and Hold No. 1 flooded, the results would have been catastrophic.

The question is, of course, did this happen? The New York Times reported that a “freak storm” crossed her path a day after leaving port. But the Poet had ridden out many rough weather patterns before with the same hatch problems.

It was not considered likely that the Poet sank due to structural failure in heavy seas. However, the Coast Guard did mention the possibility of the North Wall Phenomenon. The North Wall is the area of the Gulf Stream northwest and north of Bermuda where its warm waters collide with the cold Atlantic. This creates volatile conditions. Waves and winds are more turbulent due to the drastic changes, and these could take a vessel unawares. Another danger created in these conditions is the “Rogue Wave.” The name is very explanatory; it doesn’t travel with the pack, comes from a different direction, is out of proportion, and its actions are swift and violent.

It was estimated that on the 25th the Poet should have been in the area of the North Wall. On the 26th of October, the day the mysterious auto alarm signals was picked up in Baltimore, Mr. Bart Dunbar sighted a rogue wave 40 to 50 feet high which came out of nowhere and sank his ketch the Wandering Angus. Mr. Dunbar survived, however. So did the crew of the yacht Polar Bear which was on its way to New York from Bermuda. It seems ironic that the huge Poet vanished. Half a dozen freighters were in her vicinity, yet none reported any signal from her or sighted any debris.

Was that brief and mysterious signal received at Baltimore from the Poet? It is impossible to say. It is interesting to note, however, that several other disappearances in The Bermuda Triangle were followed by terse signals that abruptly ended before they could shed any light on what had happened. Disappearances elsewhere in the world do not seem to be accompanied by this frustrating phenomenon.

The answer to the Poet, of course, will never be known. The Poet will continue to ghost along in the annals of sea mysteries, uneasy and unsolved, just like the sea itself.

|