|

|

|

Although the Bermuda Triangle looks like just a bucket of water when compared to all the oceans of the world, it does in fact cover approximately 1,500,000 square miles, roughly 500 thousand square leagues of sea. In order to understand and fully evaluate the mystery, it is necessary to go on a journey, a journey not just below but above, through archipelagoes, on islands and over open seas; through time and tempest, from the age of creaking caravels to modern fiberglass yachts, for no other place has had such a long and mysterious heritage. So let’s put on our Seven League Boots and begin. seas; through time and tempest, from the age of creaking caravels to modern fiberglass yachts, for no other place has had such a long and mysterious heritage. So let’s put on our Seven League Boots and begin.

The first leg of our journey is to Bermuda. To give

|

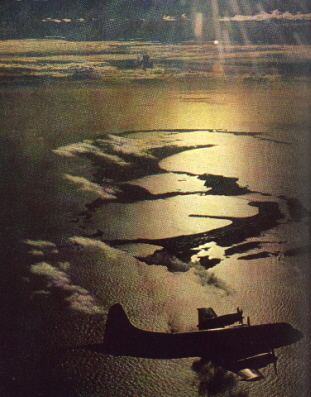

On approach to Bermuda. In like manner arrivals have seen Bermuda yet vanished before landing, without signaling any distress. (The shadowy mass at the top of the picture is not land but some of Bermuda’s dangerous surrounding reefs).

|

you an idea of its isolation, the closest landfall is the Carolina coast, about 650 miles to the northwest. By charter plane one sees nothing but hours of ocean, of winds rippling the sea and churning the swells into white caps and streamers.

Bermuda finally becomes visible much like a verdant oasis would in a desert of sand. Main Island, commonly referred to as “Bermuda” by non islanders, is surrounded by a myriad of small islets which form the tips of the Bermuda seamount.

Due to its isolation, boating to Bermuda is limited to professional “white water” sailors, as in the famous Bermuda Yacht Race, or charter vessels/cruise ships, freighters and, for air traffic, the big airliners. Aside from the scheduled traffic, few amateurs dare to challenge the wild Atlantic.

Ironically, fewer disappearances occur around the Triangle’s namesake than in other parts of its legendary seas. Those that have, however, remain some of the most fantastic and intriguing disappearances in the annals of the sea. They were not small boats manned by amateur sailors taken unawares by a fickle sea. They were these very same scheduled, large freighters and airliners. They were manned by expert crews familiar with the seas and  skies of the Atlantic, not amateur bunglers attempting a personal quest of a lifetime. skies of the Atlantic, not amateur bunglers attempting a personal quest of a lifetime.

But the sea is rough for anyone . . . and the waters off Bermuda are particularly treacherous, with seas and winds colliding with shallow reefs. Below lie countless wrecks of sailing ships

and the Spanish treasure fleets. Curious spars and beams stick up from the sea floor concealing tales and treasure. Lying with equal grace are the silent hulks of hapless freighters, dispatched to the bottom as the result of the reefs, a storm, or the carnage of war.  They rot below, a putrid color green, with great gashes in their sides, inspected by lazy fish and divers. They groan and creak with the currents and issue streams of bubbles from their gaping wounds. They rot below, a putrid color green, with great gashes in their sides, inspected by lazy fish and divers. They groan and creak with the currents and issue streams of bubbles from their gaping wounds.

But nowhere can be found the British

|

A side paddle wheeler, sunk about 1860 on Bermuda’s reefs.

|

airliners Star Tiger or Star Ariel, both of which vanished over these waters. Star Tiger disappeared in 1948 while approaching the islands, and Star Ariel vanished in 1949 not long after takeoff, in the moments between shifting radio channels to pick up her new control. On March 18, 1960, a sleek F-104 military jet took off with others, and yet it was  neatly snatched, alone out of all the others, and the other pilots did not even witness what happened. It ascended into the overcast and vanished from the squadron. Whatever happened, it happened quickly. Radar did not even pick up the aircraft descending or falling to the sea. neatly snatched, alone out of all the others, and the other pilots did not even witness what happened. It ascended into the overcast and vanished from the squadron. Whatever happened, it happened quickly. Radar did not even pick up the aircraft descending or falling to the sea.

The same can be

|

Map of Bermuda, her reefs, and the known wreck sites. National Geographic.

|

said for the ships. They disappeared suddenly. Some left minimal wreckage indicating some horrendous disintegration occurred, like the 590-foot Sylvia L. Ossa in 1976. Others left no trace at all, like the 520-foot Poet in 1980.

All of them disappeared without one peep, in fair weather, or in weather they should have breasted well, with no remains left behind, except for the Ossa which passed into oblivion leaving behind a dramatic clue: her tattered wood sign reading “L. Ossa.” Every clue uncovered in their investigations points to the fact they should have been able to send a Mayday.

Before dying and slipping below, ships have screamed their death knells. SOS calls told of the foundering of the Israeli freighter Mezada in 1982, as with the 450-foot Elma Tres. These calls enabled rescuers to save what life they could. But where are the SOS calls from those that have vanished?

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is one of the Triangle’s enigmatic cornerstones. None of the missing have sent Maydays. If they have, they were truncated, panicked calls for help, Maydays that are suddenly cut off by destruction but most certainly always by mystery. No one knew what happened to the F-104 in 1960. Searchers skimmed over a now-rain swept ocean. Then they darted to soar at the highest altitudes in an attempt to find contrails. Nothing. An emergency  “squawk” alarm was picked up, but it was traced to a Navy P-5M flying boat. In like manner the Poet vanished without its EPIRB signaling it had sunk. “squawk” alarm was picked up, but it was traced to a Navy P-5M flying boat. In like manner the Poet vanished without its EPIRB signaling it had sunk.

Although Bermuda seems isolated, in reality it is in the middle of an ocean swept with radio signals. Several stations ring the Atlantic, studious in their scrutiny of the airwaves. Dozens of ears listen for any hint of distress. Locations include Baltimore, Maryland, Gander, Newfoundland, Nassau, Bahamas, San Juan, Puerto Rico, the Azores, Balbao, Miami, and Kingston (Jamaica).

Should any trouble arise, aircraft are fitted with life rafts with automatic transmitters; life cushions and jackets make for very floatable and locatable debris. Floating Coast Guard stations are manned year around, plus several cutters cruise the waters. There are instances, though few, where a plane was able to ditch by such a cutter or station and the survivors were fed breakfast by their rescuers immediately afterward.

For example, in 1947 the CGC Bibb rescued all of the 69 crew and passengers of the clipper Bermuda Sky Queen, which ditched near Bermuda. Later that year a C-47 ditched near Station Delta. All were saved. So were all the crew of a Navy P2V when rescued by the CGC Coos Bay.

These comparisons are necessary to help us classify how the disappearances by contrast consistently stand out. These vanishings aren’t wrecks or statistical accidents. Vast tonnages of ships and planes have vanished without trace and without time for crew to send an indication of trouble.

|

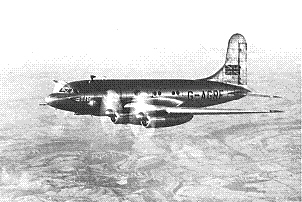

A Tudor IV, like Star Ariel

|

|

Among these sensational disappearances are huge aircraft like a Super Constellation in 1954 with 42 passengers aboard, or an Air Force KB-50 tanker, with 8 crew (1962), or a huge 8 engine B-52 bomber (1961). The Super Connie was, furthermore, carrying a particularly floatable cargo: cases of pillows, paper cups, and even a cargo of life rafts (!). Yet no debris was ever found. In 1969 a big cargo DC-4 left the Azores and disappeared as well, its messages indicating all went well in the flight until it reached, coincidentally, the area delineated as the Bermuda Triangle.

These propliners may seem dated by our standards today, but they were the mainline airliners of their time. For one of these to simply vanish back then is like a McDonnell Douglas 80 or Boeing 747 vanishing today. We have seen the world sensation caused by the disappearance of Malaysian Flight 370 in 2014. This same uproar was caused back in the 1940s and 1950s when these planes mysteriously disappeared, except it was becoming increasingly common and was not an isolated event. Not surprisingly, these incidents rated the news. People were both concerned and interested in what could have happened.

A few things were common to all of them. They must have vanished extremely rapidly, without chance to send a Mayday or SOS, and whatever happened was so mysterious so as to prevent any automatic alarm, indicating crash or sinking, and so destructive so as to prevent wreckage. They shared similar routes over the same sections of ocean . . .and they were not alone. Similar disappearances were gaining the headlines far south around the Bahamas and off the coast of Florida in the United States.

The next corner of the Triangle is Miami, Florida.

|

|